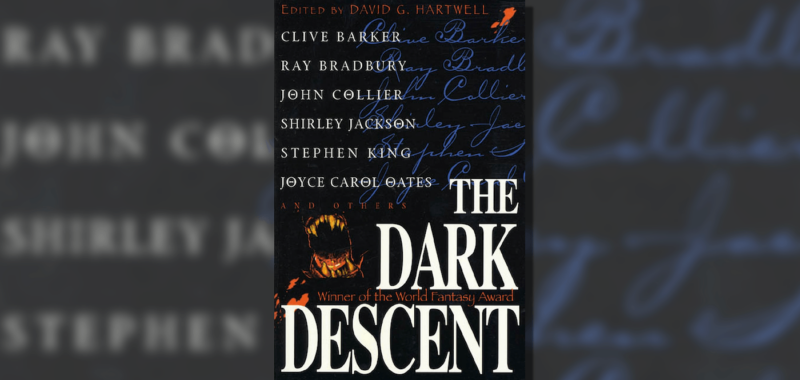

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

As we’ve seen before, Fritz Leiber has a way with the horrors of the urban landscape. His first story in the anthology, “Belsen Express,” turned an irascible right-winger’s commute into a rapidly evolving nightmare filled with hostile architecture and parallels to Nazi atrocities designed to punish him for his casual cruelty. “Smoke Ghost” evokes similarities to “Belsen Express” in structure—following an advertising executive on his way to and from the workplace and through his chats with his coworker about the idea of a “modern” ghost. “Belsen Express” offers a more moral and psychological approach, focusing more on what is wrong with the protagonist. While “Smoke Ghost” might have similar urban-gothic stylings, it takes a more existential slant, concentrating on how Catesby Wran is uniquely suited to perceive something going wrong with the world, a creeping toxicity just starting to take hold around him. In this way, “Smoke Ghost” calls back to “The Crowd” and “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs” in its exploration of a monstrous natural order, while settling itself firmly in the existential environment of Hartwell’s “fantastic” with its emphasis on unnatural aspects of the story’s reality.

Catesby Wran is an advertiser who finds himself preoccupied with the idea of a “modern ghost.” As he discusses the issue with his assistant Ms. Millick, he outlines the idea of a many-faced ghost made of soot and grime who talks in unintelligible, threatening mutterings. What he doesn’t tell Ms. Millick is that he’s seen this ghost before, a waving shapeless figure glimpsed out the window of the train home. A figure that now stalks him, appearing outside windows and as the filthy smudges that accumulate on every surface around him. It visits his psychiatrist, and shadows (pun very much intended) his family. The more the “ghost” invades his life, the more Wran becomes sure that he’s seen something he shouldn’t have, and this modern ghost will ensure he pays for that mistake in full.

Immediately from the description of a threatening, mumbling, many-faced grime creature, it’s clear that we’re dealing with something more like a god or spirit than a strict ghost the way usually we understand it. While it takes the form of pollution and grime, there’s something undeniably corrupting about it, whether it’s the way it fills spaces with gritty black soot, the unnerving way people seem to see it as a racist caricature (the psychiatrist even claims it looks like “a white man in blackface” at first), or even the way it possesses Ms. Millick at the end of the story to chase Wran up to the roof, soot dripping out of her every orifice and making her sound strangled. When Wran first describes the ghost, he specifically invokes the horrors of capitalism, worker exploitation, and the tensions and violence that come with modern industrial labor exploitation. It’s an insidious but visible symbol of the corrosion behind the modernized urban environment, gumming up typewriters and smearing windows. It also marks Wran as a participant in this world, detached though he is through his work (advertising being a potent but more hands-off wing of capitalism).

The way it marks him also ties it closer to the existential threats of “The Crowd” and “Whimper of Whipped Dogs.” The “smoke ghost” only becomes obsessed with Wran when he notices it, the same trigger as the earlier stories. The way the entity obsesses single-mindedly on Wran once it’s been spotted, threatens him directly, and will not leave him alone until it either breaks him down or kills him, speaks to the same naturalistic and hideously sapient impulses as the crowd from “The Crowd” and the infant god we meet in “Whimper”—once noticed, it reacts as if it has been threatened and must bring that threat to heel. It’s a theme common to what Hartwell calls “the fantastic,” as the darker aspects of the world only reveal themselves once someone inadvertently brushes up against some horrifying truth, once they notice or experience something beyond their understanding. It’s a nightmare that only occurs once they become aware of how unnatural the world around them is, and how terrifying the creatures that hide just out of sight truly are.

Wran is a protagonist uniquely suited to existential horror of this type. He’s a former psychic prodigy who used to perform something like remote viewing for audiences at the urging of an abusive spiritualist mother, only to suffer a nervous breakdown under stress and have his talents repressed by his father in an equally toxic manner. His “brain abnormality” (his words) and aggressive performance of normality mean that he’s already aware that things are out of joint, on some level, only to be confirmed when he’s stalked by a bizarre entity in the form of a sack of soot with eyes. Driving the point that he’s alert to the fact that the world is wrong are the moments when he has independent confirmation that the world truly is wrong—both his psychiatrist and his son are stalked by the fledgling god of industrial capitalism—completely neutralizing the idea that somehow, he’s making this all up or is otherwise delusional. He’s rational, he’s just also completely aware of an unspeakable wrongness pervading existence.

Underscoring this is the way the spirit makes its final attack on Wran. It possesses his administrative assistant, turning her into a super-strong vessel of corruption that can bend metal with its fingers and talks in a choked voice. Chillingly, there’s nothing particularly out of place about its attacks. It pulls apart the metal clasp of a purse to open it, its taunts are delivered in a cloying parody of concern, and it even turns Ms. Millick’s commonly used phrase of “Why Mr. Wran” into a terrifying verbal tic as it stalks and chases Wran up to the rooftops where this all began. It’s all horrifying, but in a way that perverts and corrupts “the real” to its own ends. It shows exactly how much control it has over Wran’s desperate bid at leading a normal life.

Rather than see Wran consumed by the horrors he’s now aware of (as in “The Crowd”) or gleefully becoming part of them (as we see in “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs”), he has a far grimmer but more appropriate fate for an existential horror story—he must live with the knowledge that the awful modern god who has hunted and terrorized him can only ever be temporarily pacified. His bowing obeisance to the “smoke ghost” is merely a tactic to keep it from killing him on the rooftop, the creature vanishing into the night with Wran fully aware that it’s going to be back. In a sense, it’s even more cynical than “Whimper.” The ending of “Whimper of Whipped Dogs” left its main character with the sense that the god was protecting her. In “Smoke Ghost,” the titular entity can never be fully pacified. It will never fully leave. It will always want more.

That ambiguity, ending on a grim question rather than a conclusion, is what puts “Smoke Ghost” squarely in the realm of “the fantastic.” The capitalistic corrosion represented by Wran’s spectral stalker will never be defeated or go away. There can be no definitive ending, no moral. At the end of the story, there is only what is, the knowledge that the world itself is wrong in ways we cannot normally see. In our case (and that of Catesby Wran), seeing it means fighting the wrongness we are aware of endlessly, with only uncertain moments of calm, knowing that even pacified, it will be back for more.

It’s horrifying, but when the alternative is worse, what else can we do?

And now to turn it over to you: Is “Smoke Ghost” more pessimistic than “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs?” Is the titular ghost more a metaphor for capitalism or industrialism? Is “obeisance” a word I should be trusted to use? Is there a favorite Fritz Leiber horror story of yours you wish had ended up in this anthology?

Please join us in two weeks for “Seven American Nights” from master of the utterly weird story, Gene Wolfe. See you then.