Boy and the World (Portuguese: O Menino e o Mundo) (2013). Written and directed by Alê Abreu. Art direction by Priscilla Kellen. Music by Ruben Feffer and Gustavo Kurlat.

Back in 2010, Brazilian filmmaker and animator Alê Abreu was working on a very ambitious project: an animated documentary titled Canto Latino. That never-finished film would have presented the sweeping story of the post-colonial hardships and growth of Latin American nations. In an interview with Variety, Abreu described the political ideas he wanted to showcase: “I asked myself during my research for Canto Latino how these Latin American countries, born as exploited colonies with such difficult ‘childhoods,’ and marked by military dictatorships that served specific economic interests, came into today’s globalized world.”

Abreu didn’t end up making that film. He made Boy and the World instead. Because, it turns out, the difference between a wide-ranging political documentary and a whimsical child’s adventure story is a matter of perspective.

This is the first Latin American film I’ve written about for this column, which is a shameful oversight considering that I’ve been doing this for over a year. I do in fact try to include films from all around the world, although that’s sometimes easier said than done, as it’s a combination of who was making sci fi or speculative films at what point in time, as well as what is available online and relatively accessible to watch. Regular readers have probably noticed that I keep stretching my definitions of both “sci fi” and “relatively accessible,” but we’re all here to enjoy movies from around the world, so I hope nobody minds.

Before we get into that, let’s take a very quick look at the history of Brazilian cinema.

There has been filmmaking in Brazil for as long as there has been a filmmaking anywhere. Mere months after the Lumière brothers presented the first public screening of a film in Paris in 1895, one of their Cinématographes (combination camera and projector) was being showcased in Rio de Janeiro. This caught the attention of Alfonso Segretto, who acquired one of the contraptions for himself and set about becoming (probably) Brazil’s first filmmaker. Segretto started out filming short clips of real events, but he eventually branched out into what film historians describe as “filmed recreations of notorious local crimes”—or what anybody who has ever succumbed to a Forensic Files marathon would recognize as true crime.

Film flourished in Brazil in the early years of the 20th century, but it took longer for it to become a broader cultural or economic force. The reason is simple: you can’t really build a widespread film culture in public cinemas without a stable power grid, and Brazil in the early 20th century did not yet have one. There were cinemas in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, however, and some early films did become popular. The film generally regarded as Brazil’s first hit was Francisco Marzullo and Antônio Leal’s Os Estranguladores Do Rio (The Stranglers of Rio) from 1908, a 40-minute true crime drama about the murder of a teenage boy.

It’s hard to find information about Os Estranguladores; I’m not even sure how much, if any, of the film survives. A runtime of 40 minutes means it would have used multiple reels of film, but I haven’t found any details about its production. (That information is probably out there, but not in a place I can easily find before this article’s deadline!) That wasn’t quite unheard of; in Australia Charles Tait’s 1906 film The Story of the Kelly Gang ran for 70 minutes on more than 4000 feet (1200 meters) of film. But films of longer than a single reel were extremely rare in the first decades of the 20th century. A 40-minute narrative film was a truly unique accomplishment in 1908.

It was also a largely insular accomplishment. Early Brazilian films were rarely viewed outside of Brazil, even though Brazilian filmmakers were making a lot of them, and kept making a lot of them through the first half of the 20th century. Brazil imported a lot of foreign films—particularly from the United States—and Brazilian films tended to echo what was popular in Hollywood during that time, such as comedies, musicals, and epics. This included the wildly popular chanchada films, the joyfully theatrical musical comedies that propelled singer and actor Carmen Miranda to fame. Miranda was born in Portugal but lived in Brazil from before her first birthday, and she is generally acknowledged to be the first Brazilian performing artist to gain international recognition. That’s resulted in a somewhat complicated legacy, as international audiences associated Brazilian entertainment with Miranda’s image long after both the nation’s arts and the woman herself had evolved beyond what made her famous.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that Brazilian films began to intersect more directly with international films. Brazilian filmmakers, like everybody else in the film world, became enamored of developments in post-World War II cinema, particularly our old friends in Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave. The Brazilian take on this filmmaking era is known is Cinema Novo, which began by exploring gritty realism about social issues, such as Glauber Rocha’s Black God, White Devil (1964). At the same time, Brazilian film—like all Brazilian arts—was complicated by the 1964 military coup and dictatorship that followed. Complicated, but certainly not stopped. Some Brazilian filmmakers left the country due to the government’s censorship, but others remained and found ways to create stylized, ironic, and symbolic protest art under the nose of the regime. That included a bizarre but notable detour into politically-themed cannibal films. No, really. You can go watch Nelson Pereira dos Santos’ Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francês (How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman) (1971) if you don’t believe me. But you should always believe me. I never joke about cannibal films.

Brazilian filmmakers kept making a lot of movies during the 21-year dictatorship, many of them state-sponsored, and some of those films did gain some international attention from filmmakers, festivals, and critics, if not from general audiences. The problem is, a strictly censored, state-sponsored film industry is a rather fragile thing once the regime that controls it ends. Brazilian cinema fell into a sort of fallow period in the ’80s, with movies struggling due to the lack of state support and the widespread popularity of television. But filmmakers kept making movies, because if we’ve learned anything from the history of film around the world it’s that filmmakers always keep making movies. This included some very good ones; Héctor Babenco’s Kiss of the Spider Woman (O Beijo da Mulher Aranha) (1985) was an international sensation—albeit one that even many cinephiles mistakenly think of as an American film, even though it was an independent American-Brazilian co-production that was filmed in São Paulo and had an Argentine-Brazilian director.

It wasn’t until the release of Walter Salles’ Central Station (Central do Brasil) in 1998, followed by Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund’s City of God (Cidade de Deus) in 2002, that Brazilian cinema finally started getting lasting attention outside of Brazil. That’s rather late for a nation that has been making feature-length films for longer than just about anybody else. The economics and influence of Brazilian cinema have gone through a lot of ups and downs, but the movies and the filmmakers have always been there, even when the rest of the world wasn’t paying attention.

That film history is long, but it’s rather spotty when it comes to animation. The first feature-length Brazilian animated film was Amazon Symphony (Sinfonia Amazônica), a black-and-white film which was entirely created by Anelio Latini Filho over the course of five years before its release in 1954. The film is similar to Disney’s Fantasia (1940) in structure: an anthology that tells stories from folklore with musical accompaniment. But unlike Fantasia, Amazon Symphony does not seem to have been part of any expansion in the popularity of animation; there are very few animated feature films in Brazil’s film history, and fewer still that survive intact. Another early example is Piconzé (1973), made by the Japanese-born animator Ypê Nakashima, and there have been various children’s cartoons and television series over the years. Another significant Brazilian animated film came along with Clóvis Veira’s Cassiopeia (1996), which has the honor of being the world’s second fully computer-animated feature film; John Lasseter’s Toy Story (1995) beat it to the title of first by a few months.

I have brought you through this abbreviated summary of Brazilian cinema not because it all leads in some obvious way to this week’s film, but because it doesn’t, and that in itself is curious. We’ve watched many films that grow organically out of cherished cinematic traditions; The Iron Giant (1999) is the perfect example, as it is an homage and a love letter to both American sci fi cinema and animation from earlier eras.

Boy and the World is different. Neither its storytelling nor its artistic style is obviously inspired by trends in Brazil’s long cinematic history. In fact, Abreu has specifically cited another unusual film as the inspiration that got him excited about animation at a young age: René Laloux’s Fantastic Planet (1973).

As I said above, the process that led to Boy and the World began when Abreu was developing a wide-ranging political documentary. He was going through his sketchbooks when the scribbled, scratchy drawing of a young boy caught his attention. That was when he started thinking about telling that big political story—the story of urbanization, industrialization, and wealth inequality in post-colonial Latin America—from a child’s point of view.

I think that anybody who writes fiction can recognize that lightbulb moment that happens when you realize that changing the point of view changes everything about your story. I don’t know what Abreu’s Canto Latino would have looked like, but I’m glad he was seized by a wild fit of creativity that inspired him to rework his entire approach.

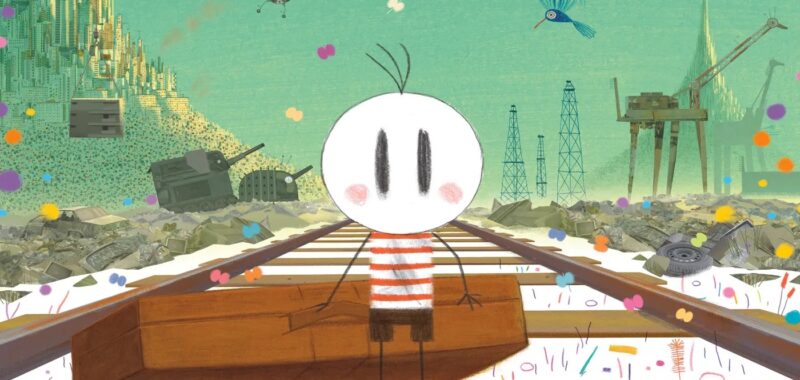

Because Boy and the World is a marvel. It’s beautiful, poignant, and painful. It tells the story of a boy and a nation in a way that is both loving and critical. The parallels between a child searching for his father and a nation searching for its identity are deliberate and powerful. The film begins, as a child’s life begins, with a small, protected world of innocence, one full of color and wonder in the countryside. When the child leaves his home, that world expands to include the precarious lives of migrant farm laborers, the toil of exploited factory workers, and the weary anonymity of life in a favela, as well as clashes between protesters and military troops, a glimpse of the futuristic cities across the ocean that benefit from unseen human labor, and the persistence of a creative, rebellious spirit in the most crushing of circumstances.

It’s all in there, so rich and vibrant, and conveyed without any words, because the film has no dialogue. Some characters do speak a little, but the Portuguese dialogue is muddled and played backwards, giving viewers a child’s sense of experiencing but not fully understanding adult conversations. In place of the dialogue is music. The soundtrack is the work of Brazilian composers Ruben Feffer and Gustavo Kurlat, who made a point of creating an immersive soundscape in which the sound effects of the film—everything from the birds to the factories, the storms to the protest marches—are part of the score.

Among the musicians they brought on to create the soundtrack was the legendary Brazilian percussionist Naná Vasconcelos. In an interview with Billboard, Abreu talks about the ingenuity Vasconcelos brought to the film’s score, such as using unique instruments and recording in a dynamic, improvisational way. Equally important, however, was to bring the film back down to earth at the end, which is why it ends with a song by Emicida, a rapper out of São Paulo’s underground hip hop community, a choice that Abreu describes as a deliberate nod to Brazilian protest music of the past.

The film doesn’t need dialogue—nor does the audience need in-depth knowledge of Brazil’s history—to understand the significance music plays in political protest. The message is there every time the colorful parade appears and every time the music endures when other sounds try to drown it out.

And we can’t talk about Boy and the World without talking about its art and animation. The style is unique for an animated feature film, and it’s one that Abreu and art director Priscilla Kellen sought to preserve throughout the story. That meant maintaining not just the childlike simplicity of the forms but also the visual textures of the tools of childhood art: crayons, markers, colored chalk, watercolors, cutouts. Some scenes are as simple as a single figure on a blank white background, while others are an ornate symphony of colors and shapes. What we see on the screen is a combination of hand-drawn images in different media and layered computer animation, which allows even the roughest drawings to move and interact smoothly.

All of the art is beautiful, and some of it is truly breathtaking. A few of my favorite visual elements are tied in with the film’s larger themes. I love that every machine is portrayed as an animal, from the trains and trucks to the long-necked dinosaurs that make up the shipping port. It is exactly the sort of imagery we might expect from an imaginative child experiencing a world of unknown rules, but it’s also a nod to the process of industrialization, particularly when paired with the clever, machine-like patterns that develop from the work of the human farm and factory laborers.

It’s not a subtle point, nor should it be. There are humans driving the massive economic machine that feeds endless goods to the ravenous floating cities across the ocean. The gears might change, the process might evolve as workers are shunted from one part of the system to another, from the cotton fields to the factories to the cities and back again, but they are always there. The machine doesn’t exist without them.

There is a brief section late in the movie when the animation is replaced by real footage of destructive industrialization and deforestation. This is, again, not a subtle choice. It’s a way of contextualizing the whimsy, a way of reinforcing that what is rendered so beautifully in crayon drawings is, in fact, representative of a rather ugly reality. The characters in Boy and the World do not have realistic faces and many are not distinctive; they are not individuals but symbols of entire populations. All of the men who spill from the train are identical and it’s impossible for the boy to recognize his father, because they are every father who left his family due to economic necessity. They are every family torn apart by the juggernaut of so-called progress.

And the boy’s journey is not a childhood adventure. It is the story of a lifetime, as we see when we reach the end and the boy is an old man returning to his rural home. It was never going to end with the family reunited; it’s simply not that kind of tale. The hardships of the world are too present, for all the charm and wonder that goes along with them.

Boy and the World is a beautiful movie. It’s also sad and painful in a way that leaves the heart aching. I adore the art and animation style, and even more I love the juxtaposition of the childlike perspective, bright imagery, and heavy themes. Some of the scenes that stick with me are the moments throughout the film that emphasize the importance of art in times of hardship: the impoverished father playing his flute, the factory worker spinning color and music amidst dreary oppression, the determined march of protesters, the way that people throughout the story, old and young, find their community and voices by making music together. It’s a rare and lovely accomplishment, I think, for a film to tell a story so well, with so much heart, without any words but with perfect understanding.

What do you think of Boy and the World? Thoughts on its art, its music, its story? I wasn’t sure what to expect when I picked it to watch; all I knew was that it was a darling among critics and film festivals. This is one case where choosing a movie on a whim seems to have worked out quite well, as I think it’s wonderful and I’m very glad to have found it.

Next week: The insects are coming and we are not ready for them. Watch Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) on Max, Amazon, or Apple.