There’s a common perception in the U.S. that taking public transit is dangerous. Headlines blare gruesome reports of people getting pushed in front of subway trains or attacked by strangers, stoking fear and anxiety. Last month President Donald Trump’s secretary of transportation threatened to withhold funding from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority—which runs the New York City subway and other public transit in New York State and Connecticut—unless it provided plans to reduce crime on the system.

But in reality, a closer look shows the safety risks of taking public transportation are relatively low. According to the data, driving a car in the U.S. is far more dangerous than taking public transit—in terms of crash risk and crime.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Public transit travel requires people to travel with strangers in a confined space, and especially in large cities with very diverse populations, it’s easy to feel intimidated by that experience,” says Todd Litman, founder and executive director of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute in British Columbia, who has published numerous studies on public transit safety. “Just from an experiential perspective, it feels unsafe, especially to people who don’t do it frequently.” The technical term for fearing a risk despite it having a low probability is dread, he says.

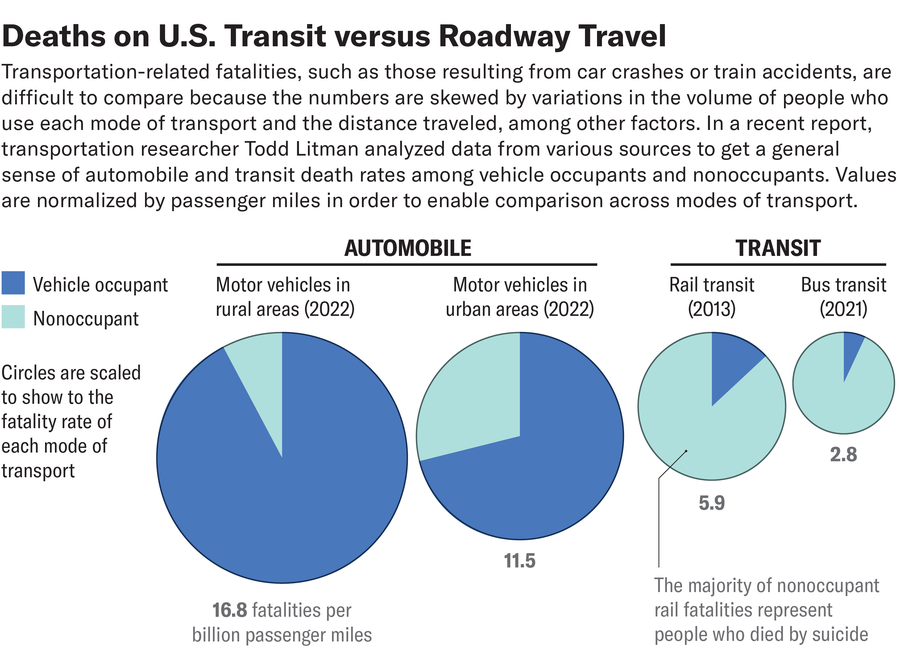

Yet Litman’s research puts public transit’s death or injury rate at about one tenth that of car travel. And neighborhoods oriented more around public transit have about one fifth the overall traffic deaths per capita of car-oriented neighborhoods.

One important factor is that communities with better public transit often tend to also be more compact and walkable or cyclable, which makes them safer. Additionally, access to public transit reduces the number of people who engage in risky behaviors such as being intoxicated or texting while driving because they have alternative forms of transportation.

Data from the nonprofit National Safety Council suggest the safety difference between public transit and driving is even greater. The rate of car deaths per 100 million passenger miles in recent years was more than 50 times that of buses, 17 times that of passenger trains and 1,000 times that of air travel.

“Every time we get in the car, we face an enormous threat to our safety,” saysNatalie Draisin, director of the North America Office and United Nations representative for the FIA Foundation, a global philanthropy organization focused on road and travel safety. The U.S. is “the high-income country with the highest road traffic fatality rate, and we just accept that.”

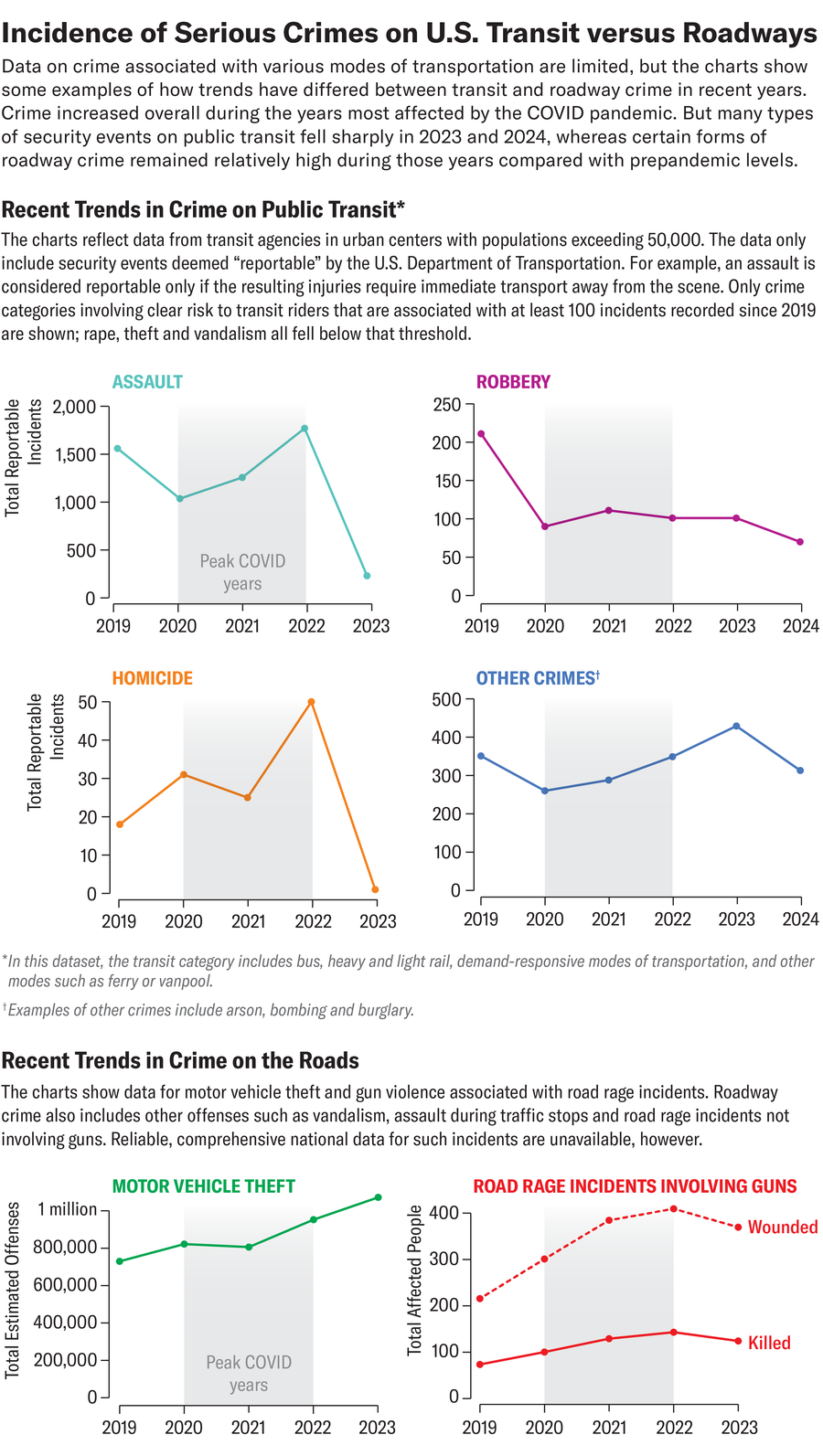

Even from a crime standpoint, public transit is generally safer than driving. Crime on public transit did increase during the COVID pandemic, in part because there were fewer people taking it, experts say. But the total numbers of reported transit crimes—including assaults, robberies and homicides—were still relatively low and orders of magnitude lower than road crime. Vehicle thefts, along with road rage incidents involving guns, also increased during the pandemic, data show. Road-related crime can also include assaults during traffic stops and road rage incidents that don’t involve guns, but data on these types of crime are harder to quantify.

Amanda Montañez; Source: Bureau of Transportation Statistics (transit crime data); Federal Bureau of Investigation (motor vehicle theft data); Everytown for Gun Safety (gun violence data)

Many experts largely blame media approaches to coverage for the perception that public transit is unsafe: news reports tend to focus on rare but sensational incidents such as subway assaults, as opposed to routine ones such as car crashes. “When somebody gets pushed onto a subway track in New York City, that is national news,” Litman says. But “on any day there are people who are injured or killed in road rage incidents, and that is local news.”

Draisin agrees. “If you think about something that happens on a subway platform, it’s very individual. It’s very visible to other people; it’s very personal. And it’s so rare that it’s shocking,” she says. “Whereas a crash on the road every day, because it’s so frequent, just doesn’t have the same kind of shock value anymore.”

Litman says racism and classism may also contribute to perceptions of public transit’s dangers. Many Americans associate taking public transit with “poor people” and immigrants, he says. Additionally, Americans often idealize car-centric suburban life, which adds to the perception of car travel being safer than it really is. But in terms of traffic deaths, Litman says, “if you’re looking for safety, the worst thing you could do is move out to thesuburbs.”

Another part of the problem, he adds, is the way public officials often try to promote safety on public transit. Many transit systems have public service announcements that warn riders, “If you see something, say something.” Litman says this can prime people to worry that there is more reason to be afraid.

Litman thinks this approach fails to address the relative safety of using public transportation. “The first statement should always be [that] traveling on public transit is super safe, and [PSAs should] provide some statistic about that,” he says, “and then say, ‘But we’re trying to make it even safer by doing these safety strategies and encouraging passengers to report possible risks.’”

Officials can also emphasize benefits of public transit; for example, it can expose people to more opportunities for pleasant social interactions. In a 2014 study, people taking the train or bus who were instructed to interact with a stranger next to them reported a more positive experience than those who had no interaction—even though they had expected to feel the opposite. In an era when loneliness is one of the biggest threats to people’s health, commuting by public transit can provide a source of routine, if fleeting, human connection.

As safe as public transit is, there are many things transit authorities can do to make it safer. More street lighting could be added around stops or stations, for example, and on-demand stops could be allowed on more buses. Transit systems could also hire more female drivers, which Draisin says helps to make them feel safer for women—who, globally, use public transit more than men. Systems should have zero-tolerance policies against sexual harassment and ensure there are clean restrooms and places to breastfeed or change diapers, she adds.

The U.S. also needs to invest in public transit quality, according to Litman. Too often, it is dirty and unreliable. Systems in many European and Asian countries are clean and modern, which encourages more people to use them.

Driving can be made safer, too, and one of the best ways to do that in cities is by reducing vehicle speeds. Last year New York City passed Sammy’s Law, which reduced speed limits in certain areas, particularly school zones. Early data suggest that New York City’s congestion pricing program (which took effect in January and automatically charges drivers a fee when they enter chronically congested areas), has already reduced crashes and injuries. And at least 19 states, along with Washington, D.C., have passed laws allowing speed cameras. Trial studies are underway across the U.S. for systems that automatically limit vehicle speed, a concept known as intelligent speed assistance.

Even with these improvements, investing in public transit remains one of the best ways to make travel safer for everyone, Draisin says. “If we disinvest from that,” she says, “we’re going to threaten everybody’s safety.”

IF YOU NEED HELP

If you or someone you know is struggling or having thoughts of suicide, help is available. Call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or use the online Lifeline Chat.