“Gothic” movies have been around for a long time, hitting a peak in the early days of cinema with horror films like Tod Browning’s Dracula and James Whale’s Frankenstein. But the style fell out of favor in the 1940s as filmmakers focused on more contemporary settings and moved on from adapting classic literature to exploring more modern ideas. Hammer Film Productions brought the gothic back in the late 1950s and 1960s, with bloodier scenes and slightly racier subtext, updating the original monster movies for a more liberated audience. But as the years went on, horror once again pivoted away from more historical settings to contemporary or futuristic stories, often moving the typical tropes to settings like small-town USA or even outer space.

In the 1990s though, things shifted once again, bringing a resurgence of gothic films that captured the attention of audiences and spilled out into the culture at large. The “gothic” in this context is not necessarily the same as the “Gothic” in literature: Though there are some overlapping themes in both genres, the films are ultimately more concerned with aesthetics than being bound by strict thematic guidelines. For instance, many Gothic novels often feature unreliable narrators, conflicting points of view, and convoluted narratives, telling stories through a variety of techniques (such as the epistolary structure of Dracula). Films borrowing from the genre typically tell a more straightforward story, streamlining the plot while keeping the moody and tense atmosphere.

As the “goth” subculture grew in the ’80s and became a bit more mainstream in the ’90s, there was a split in a couple of different aesthetic directions movie-wise, largely hinging on whether the film had a historical or contemporary setting. Hollywood films that skewed historical, with lavish costumes and sets, took classic horror film imagery and updated it while keeping the focus on romantic relationships and tragic circumstances. They often adapted older novels and works of fiction, keeping the basics of the text and layering in images or characters that felt a little closer to what ’90s audiences looked for, with healthy doses of romance to broaden their appeal.

For me, a teenager who had just seen the musical adaptation of The Phantom of the Opera on stage, thereby getting my first taste of opulent costumes and sets coupled with murder and forbidden love, the advent of these gothic films hit at the perfect time. The films of the era inspired and transported me, awakening a lifelong love of both horror and romance that only grows with each coming year. But my heart always comes back to these 1990s goth movies, so I hope you’ll join me for a closer look at the key films of the decade…

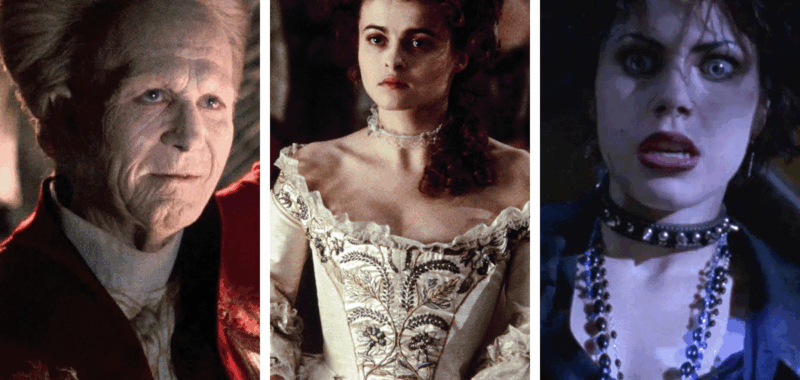

The first film in the gothic genre I remember seeing was Francis Ford Coppola’s update of the quintessential vampire novel, Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). The adaptation was one of the top 20 films of the year at the box office, and it spurred a loose trilogy of highbrow, auteur-led films that mined the classic horror library. After Dracula, Coppola served as executive producer on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994), directed by and starring Kenneth Branagh. Mary Reilly, Stephen Frears’ take on The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, followed in 1996. While I love all three films, for many people, myself included, Bram Stoker’s Dracula set the historical gothic horror romance bar pretty high.

The 1992 production directed by Coppola brought a lush, gory, and sensual style to a story that was familiar to legions of horror fans. Stoker’s epistolary novel had been adapted a number of times previously, with varying levels of horror and romance in the mix, from Tod Browning’s 1931 film starring Bela Lugosi to Frank Langella’s turn as the Count in 1979’s Dracula.

What sets Coppola’s version apart is the balance of sex and violence. You can’t have one without the other; the act of bloodletting is as necessary as the act of lovemaking, and these two facets of the story are explored much more explicitly than in previous adaptations. The decision to begin the film with a backstory is crucial to this balance. Dracula’s (Gary Oldman) renunciation of God when he finds out his love, Elisabeta (Winona Ryder), has taken her own life is portrayed as an incredibly romantic gesture, and it is immediately followed by a literal fountain of blood. Dracula’s entire raison d’être becomes consuming blood to prolong his existence, crossing “oceans of time” as he searches endlessly for his lost soulmate.

This push and pull between sex and death plays out throughout the film. When Dracula’s brides materialize in Jonathan Harker’s (Keanu Reeves) bed, they don’t just want to suck his blood, they want to defile him as well. And when Mina (Winona Ryder) finally discovers where Lucy (Sadie Frost) has been disappearing to at night, we see a woman in the throes of sexual passion while also being attacked by a monstrous, wolf-like creature. The blending of romance and blood, sex and violence heightens the dramatic tension of the film, and creates a grand spectacle that left a lasting impression on me when I saw it (too young) for the first time.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein uses a similar blend of romance and violence to tell the story of Victor Frankenstein and his creature. The script for this version of the movie enhances the romance element of the story with plot points drawn from the James Whale film sequel, The Bride of Frankenstein (1935). Victor’s love life is featured more prominently, with Helena Bonham Carter playing Elizabeth, his adopted sister and eventual wife (an incestuous-adjacent pairing that echoes relationships in many Gothic novels). Victor wavers between wanting to spend time with Elizabeth and focusing on his research, seeking to overturn death. He abandons Elizabeth long enough for Victor to create life in the form of the Creature (Robert De Niro), and then he promptly abandons his monster and runs back to his lover. Unlike previous Frankenstein films, Victor does seem to genuinely care for Elizabeth. In contrast, Peter Cushing’s version of the character in Hammer’s The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) blatantly cheats on his fiancée and doesn’t seem much interested in her at all.

That love and desire for Elizabeth is part of why this ’90s gothic take fits so well into the films of the era. There’s a bit more sex and a lot more shirtless Kenneth Branagh on the screen in this version, and the heightened drama amplifies the shock of the eventual violence. The climax of the film comes when The Creature bursts into Victor and Elizabeth’s honeymoon suite. The monster had tracked down the doctor, asking him to create a companion with whom he can share his undead life. When Victor betrays his promise, the Creature murders Elizabeth, literally ripping her heart out, so Victor can feel the same pain the Creature feels. The grieving doctor decides he has no choice but to reanimate his lover, with disastrous consequences.

Hitting theaters only a week after Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Interview with the Vampire isn’t part of the unofficial ’90s trilogy of adaptations of classic 19th-century Gothic horror that would be capped off by the release of Mary Reilly in early 1996, but it definitely shares many of the same sensibilities, regardless of its source material. The Brad Pitt/Tom Cruise film adapting Anne Rice’s popular novel was plagued by production issues and even criticism from the author herself, who initially hated the casting of Cruise as the vampire Lestat de Lioncourt. Once she saw the film, though, she changed her mind and threw her full support behind the actor, claiming he fully embodied her favorite creation. Cruise is arrogant and cruel, seductive and charismatic as a vampire in search of a companion to share eternal life with him. The man he finds is Louis de Pointe du Lac, played by a dramatically morose Brad Pitt.

Louis is mourning the death of his wife and thinks he has nothing left to live for; in other words, he’s a perfect mark for a monster like Lestat, who manipulates Louis into agreeing to become a vampire. The two embark on a centuries-long toxic relationship, unable to leave each other and hating most of the time they spend together. Not even the introduction of a “daughter” can save their broken family unit for longer than a few decades. When Lestat turns Claudia (Kirsten Dunst) into a vampire at the age of ten, he didn’t consider that she would be stuck in the body of a child even as her mind aged, and her resulting resentment over being treated like a kid and unable to pursue real love ultimately breaks up the family dynamic.

This is such a messy, messy film, and one of my favorite examinations of toxic relationships on almost every level. Lestat and Louis, Lestat and Claudia, Louis and Armand (Antonio Banderas) …everyone is miserable and they take it out on each other in deliciously awful ways. Apparently, director Neil Jordan’s decision to film only at night (fitting for a vampire movie) made Brad Pitt so depressed that his character’s fog of despondence wasn’t entirely an acting choice. The classic gothic themes of curses from the past and unreliable narrators are both at play in Interview. The film uses the titular interview as a framing device, so we’re never quite sure if the version of the events we’re seeing is completely accurate.

These highbrow gothics had, up to this point, found a pretty healthy audience at the box office. Big name directors and actors and big studio budgets screamed prestige, and viewers responded well to the mix of violence and romance that pervaded the films. But in 1996, two things happened that brought about the end of this style of gothic film: Mary Reilly was released to middling reviews and disappointing box office, and Wes Craven shattered the horror movie landscape once again with Scream. But even though Mary Reilly was less successful than its predecessors, I think there’s value in reexamining the film.

The love story in Mary Reilly is more subdued than in either Dracula or Frankenstein, but it still simmers under the surface of this gothic romantic horror film. The story is a retelling of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, but the main character here is Mary (Julia Roberts), a maid serving in Jekyll’s house (John Malkovich plays both Jekyll and his alter ego). She catches the eye of the doctor, who is searching for a way to curb humanity’s basest instincts. He’s developed a serum that suppresses negative thoughts and emotions, but there’s a catch: when he takes it, all the worst parts of him coalesce into a separate personality: Edward Hyde. Hyde is also intrigued by Mary, but he’s a lot less shy about letting his feelings be known.

Mary is drawn to the doctor and his kindness, but she isn’t allowed to speak her feelings directly, given both the societal strictures of the Victorian Era and the class distinction between herself and her love interest. When Hyde begins to show up more regularly, Mary is shocked to discover she may also have feelings for this crass and violent man. Once again, love and violence are inextricably linked in this gothic film, and though none of these movies have happy endings, the somber tone of Mary Reilly really drives home the futility of falling in love with a monster.

That’s not to say that all the gothic films of the ’90s era ended in tragedy. For instance, there were movies like… well, at least Sleepy Hollow ends with a HEA (happily ever after, for non-romance fans). The 1999 Tim Burton vehicle for Johnny Depp is the last gasp of the Hollywood gothic (at least in big studio films) until Guillermo Del Toro’s gorgeous Crimson Peak. Retelling Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” Burton brought his signature quirky aesthetic to an American style of gothic that played up the romance between police investigator Ichabod Crane (Depp) and Katrina von Tassel (Christina Ricci), a young woman whose family secrets hold the key to a string of gruesome murders perpetrated by the Headless Horseman (I rewatched this movie last year and I was surprised by just how gory it is).

Blood and horror aside, Sleepy Hollow is a more lighthearted film than many of its predecessors. Murder and mystery abound, sure, but unlike the underlying despair that pervades the previous films discussed here, there’s a lightness that permeates the town of Sleepy Hollow. There’s no shortage of comic relief, as black as the humor is. Perhaps this is a nod to the snarky, sarcastic tone that gained in popularity when Scream and its copycats became the dominant brand of horror at the end of the decade. As the audience for horror began to skew younger again, studios leaned away from these more serious, historical films and toward a more contemporary vibe. But these new, urban-centric horror films also owed a debt to gothic sensibilities, just in a slightly different way. Let’s go back to the beginning of the decade…

On the other side of the gothic spectrum, breaking away from literary and historical inspiration, was the angsty goth movement, which drew from the aesthetics of the more modern punk, industrial, and post-punk music. In these darker goth movies, filmmakers emphasized the horror aspects, and often romance played less of a central role in the narrative (though in many movies, there is still a love story plot). Filmmakers like Tim Burton and Alex Proyas looked to capture a modern audience more excited by action sequences and superhero-style stories and added a goth look to films like Batman Returns (1992), The Crow (1994), and The Craft (1996), borrowing their aesthetics from the larger music and fashion movements of the time.

I won’t argue that Batman Returns is a true “Gothic” story—it’s definitely more superhero action film than anything else. But while director Tim Burton’s previous Batman film (1989) was a more straightforward origin story for Batman (Michael Keaton) and The Joker (Jack Nicholson), Batman Returns does feature many themes common to the gothic genre. The Penguin (Danny DeVito) curses the children of Gotham, particularly Max Shreck (Christopher Walken) and his firstborn Chip (Andrew Bryniarski). The duality of the characters is a common gothic idea. The Penguin and Shreck mirror each other in social standing and ambition; and Catwoman (Michelle Pfeiffer) and Batman are two sides of the same coin as well, fracturing their identities and choosing to fight for either good or evil.

And there’s romance here as well, a much more satisfying exploration of a love story than in the previous film in the franchise. Selina Kyle is both a worthy adversary and partner for Bruce Wayne, and the chemistry between the two is palpable. (I think the ballroom scene, where each discovers the other’s secret identity, might contain the most emotion ever shown in a Batman movie, and the Siouxsie and the Banshees musical backdrop adds yet another goth layer to this love/hate story.)

With Burton at the helm, the aesthetics definitely borrowed from the gothic end of the spectrum, as most of his films do. Catwoman’s latex costume The Penguin’s dandyism combined with his exaggeratedly grotesque features; the strange circus-themed Red Triangle gang—all of these creepy, dark images took their inspiration from the subculture that was gaining traction outside of The Cure concerts and clove cigarette-scented goth bars. The city of Gotham itself was full of architecture and scenery that wouldn’t be out of place in Tod Browning’s Dracula, with menacing gargoyles looming over the streets, Wayne Manor’s expansive castle-like rooms, and of course, bats everywhere. As with later contemporary goth films, the look of the film is almost more important to lending a gothic vibe to the movie than the storyline. Director Alex Proyas would take this look one step further in 1994’s The Crow.

Based on James O’Barr’s comic book series of the same name, The Crow is a love story, a horror story, a revenge story, and an examination of profound grief all rolled into one. Eric Draven (played by the late Brandon Lee) and his girlfriend Shelly Webster (Sofia Shinas) are brutally assaulted and murdered on Devil’s Night (the night before Halloween) by a vicious gang sent by Michael Wincott’s Top Dollar, a crime boss who wants to seize their apartment building. A year later, a crow spirit guide brings Eric back from the dead to seek revenge. Undead and seemingly invulnerable to injury, Eric tracks down the perpetrators of the attack and murders them one by one, getting closer and closer to Top Dollar and his half-sister (and lover) Myca, who are investigating this seemingly invincible vigilante. The themes of revenge, haunting, and the sins of the past are all very gothic in nature, and they permeate the entire film. Coupled with the pitch-black look of the film, it’s the ideal urban goth movie.

There’s a palpable sense of grief that settles over the entirety of The Crow, and that grief is amplified by the tragic death of Brandon Lee on set. The young actor was shot and killed by a faulty prop gun, and while the producers were able to complete filming using a stunt double, the loss of the charismatic young actor cast a shadow over the movie. Nevertheless, it’s a propulsive action film driven by a macabre supernatural story that resonated with both audiences and critics (it was the 10th-highest grossing rated-R film of 1994). The dark aesthetic and paranormal elements paved the way for other action horror mash-ups, like Blade, Underworld, and Resident Evil, and studios began to look more closely at IP they could adapt from media such as comic books and video games.

The Craft (1996) wasn’t adapted from a popular book or game franchise, but it did capitalize on a resurgence of interest in Wicca and spellcraft. This movie is generally more grounded in reality than a story about the undead or superheroes, but it’s still firmly placed on the gothic spectrum (and was responsible for my love of crushed velvet and black clothing). Sarah (Robin Tunney) moves to L.A. with her dad after a traumatic experience in her hometown. She shows up at a new school and soon makes friends with a group of outcasts: Bonnie (Neve Campbell), Rochelle (Rachel True), and Nancy (Fairuza Balk). The trio needs a fourth person so they can perform their ritual to invoke Manon, a deity who can grant them powers, and Sarah seems like the perfect recruit.

Their ritual is successful, and each person receives their wish, bringing them love, beauty, power, and revenge. But it’s not long before the girls, and Nancy in particular, hunger for more. Sarah begins to realize that maybe invoking such a potentially malevolent spirit is a bad idea, and the final act becomes a showdown between Nancy, seemingly the strongest of the four (she says she’s been blessed by Manon) and Sarah, who ultimately thwarts the rest of the coven. At the end of the film, Bonnie and Rochelle are warned against trying to challenge Sarah in the future, since unlike them, Sarah still has her powers. Poor Nancy is confined to a psychiatric ward for the murder of Sarah’s aggressive love interest Chris (Skeet Ulrich) and screaming that she can fly. The ending always fell a little flat for me, though it does incorporate some great gothic tropes (how many gothic stories feature asylums?). Nancy is given a much harsher sentence than I think she deserves, especially given that her murder of Chris comes not out of spite but because Chris tries to rape Sarah.

Aesthetically, this film is rooted in goth subculture, though it’s much more mainstream than a movie like The Crow. The movie sparked a number of clothing trends, and the mashup between private school uniforms and Hot Topic chic left a lasting impression on alternative fashion girls everywhere (myself very much included!). The Craft embraces the counterculture only as long as it doesn’t go too far; you can say “We are the weirdos, mister,” but you can’t actually harness your power and disrupt the system too loudly, or else you’ll be punished for it.

The underlying message here feels like the beginning of the death knell for the goth era. No longer interested in exploring new territory and experimenting with new genres, The Craft is much more of a safe and straightforward teen film that wears the trappings of a subversive genre but never fully embraces them. As with the historical goth films of the decade, by the end of the 1990s, the themes that felt fresh and exciting were losing their novelty and mainstream audiences began to tire of goth-heavy tropes. There were attempts to further experiment with adding gothic elements to other genres (such as 1998’s Dark City, directed by Alex Proyas), but the boom had passed and studios began looking for the next new thing.

And yet, while it may fall in and out of fashion to varying degrees, the gothic never really dies (fittingly, given all the vampires, revivification, and supernatural twists we’ve seen in just this small sample). We’ve seen remakes and sequels of a few of the films mentioned above in recent years, and the ongoing television adaptation of Interview with the Vampire, which leans even further into the emotional drama of the character dynamics than Neil Jordan’s film, is currently helping to resurrect our love for gothic horror (and deeply dysfunctional vampire relationships). With the success of Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu and the upcoming releases of Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein and Luc Besson’s Dracula: A Love Tale, we may be looking at the beginning of the next cycle of gothic horror films. As someone who’s never stopped watching these captivating ’90s goth movies, I couldn’t be more excited to see where we go from here. What’s your favorite ’90s gothic film? Have I missed an example that you love, or are you a die-hard Bram Stoker’s Dracula fan like me?